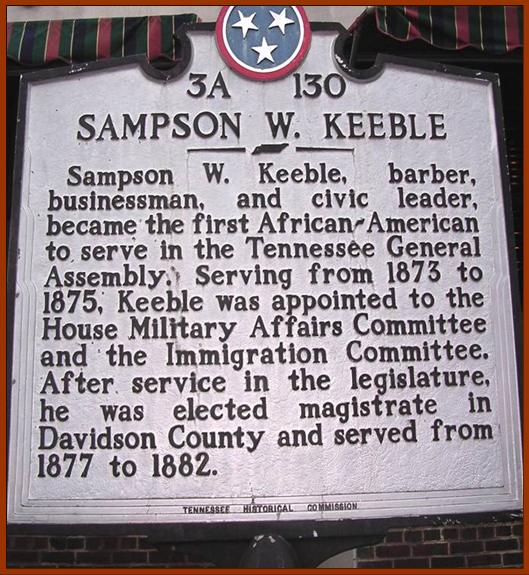

A dedicated and respected member of the Republican Party, Sampson W. Keeble was elected to represent Davidson County in the 38th Tennessee General Assembly, 1873-1874. He was the first black Tennessean to serve in the state legislature. A Tennessee Historical Commission marker in downtown Nashville, near a one-time Keeble family home on South Broadway, proclaims,

Early years in slavery

According to the date on his tombstone in Nashville’s Greenwood Cemetery, Keeble was born in 1833 in Rutherford County, Tennessee, to Sampson W. and Nancy (or Mary) Keeble. Their slave-owner’s father, Walter “Blackhead” Keeble, had stipulated in his 1816 will that his slaves were to be cared for, educated, and freed as soon as the law would allow, and that any of his heirs who did not agree to those requisites would inherit nothing – land, slaves, nor money. When Walter died, the inventory for his 1844 will listed among his slaves 11-year-old Sampson and 16-year-old Marshall (perhaps the father or grandfather of evangelist Marshall Keeble, 1878-1968). The two youngsters were inherited by Walter’s son, Horace Pinkney Keeble, a Rutherford County attorney. (At least one period newspaper named Horace’s brother Edwin A. Keeble as Sampson Keeble’s owner, but there is substantial evidence that Sampson was, in fact, part of H. P.’s household.) Also listed among Walter Keeble’s slaves, who were grouped by family, were Sampson’s mother, called Nancy Polly (40) to distinguish her from another woman named Nancy Betty (39); Sampson’s sisters Elisa Jane, 9 [the “Eliza A.” on Nancy’s tombstone], and Catherine, 2 [“Kitty”]; and brother George Lent, 6 [“Ceorce L”]; the tombstone appears to name one more child, with a name ending in “y.” That could be Joicy (six months old at the time of the inventory) or Billy Buck (age not given), both of whose names are listed near those of the Keeble family on the inventory sheet. There is no evidence that Pastor Marshall Keeble was related to this family, other than to share their slave owner’s surname.

The white Keebles always used the word “servant” instead of “slave” when referring to their workers (a common practice of Middle Tennessee slave owners), and they seem to have treated their own “servants” with extraordinary consideration. Perhaps because of their tolerant practices, the future legislator gained a measure of independence early in his life. The Nashville Union and American (December 6, 1872) stated that in 1851, when Keeble was 18 years old, he took a job as “roller boy” on the Rutherford Telegraph in Murfreesboro; by 1854 he was working as pressman for both the Telegraph and the Murfreesboro News. He may well have learned the trade under H. P. and Edwin Keeble, who owned the Murfreesboro Monitor. Sampson worked for these newspapers until the Civil War, and then, according to an account in the Union and American (November 7, 1872), “he was in the Confederate lines during most of the war.” However, he was probably, if anything, serving as an aide or manservant to Horace Keeble rather than actually carrying arms. A Clarksville paper’s statement that “he shouldered his cooking utensils and went into the Southern army like a hero” suggests that he may have been taken along as a cook.

Home and employment in Nashville

This Tennessee Historical Commission marker commemorates the service of Sampson W. Keeble, “the first African-American to serve in the Tennessee General Assembly.” It stands near the intersection of Broadway and 2nd Avenue in downtown Nashville. (photo by Kathy Lauder)

By 1865 Nashville city directories show that Sampson Keeble had settled in Davidson County. He worked in a barbershop at 24 Cedar Street (today’s Charlotte Avenue) and took various part-time jobs to support himself; family members report that he also worked for some time as a custodian in a law office, where he became interested in studying law. The attorneys in that practice, reportedly impressed by his enthusiasm for learning, supported his efforts. He was eventually able to pass the Tennessee bar, which in those days did not involve a written examination, but instead required assessment and approval by a handful of legal professionals and, finally, confirmation by a sitting judge. Keeble’s legal training would later allow him to qualify for election as a Davidson County magistrate. Family members also believe he attended Fisk University briefly, although the university cannot locate his name in their records.

Keeble participated in “a meeting of colored men,” some of Nashville’s leading citizens, who met to quash rumors that the city’s African Americans were planning “a mob and Massacre.” The group, which also included William Sumner, Carroll Napier, Peter and Samuel Lowery, Henry Harding, Nelson Merry, and others, wrote a letter to city government officials, reprinted in the Republican Banner, assuring them that the rumors were false, and that “the feelings of the colored people [were predisposed] toward peace and good order.”

Both Sampson Keeble and his brother George worked as barbers, along with several other Keebles (including a Wesley) who may have been relatives. Sampson eventually established the Rock City Barber Shop and managed it for about 20 years. (He was still listed as a barber in the Nashville city directory as late as 1885.) Barbershops of that era were strictly segregated: African American barbers were extremely popular with white customers, who still took considerable pleasure in being served and groomed by these deferential former slaves.

Many dramatic changes were taking place in the South during the early post-war years. Tennessee had returned to the Union with far fewer restrictions on its political structure than other Confederate states. The third state (July 19, 1866) to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, which granted citizenship status to African Americans, Tennessee was readmitted to the Union a week later, without ever having to conform to the stiff federal regulations most of its neighboring states faced during Reconstruction. Tennessee’s new constitution already included an anti-slavery clause, and, in less than a year (March 1867), the General Assembly would approve the right of African American men to vote and to hold political office – nearly three years before the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment.

Keeble had been an active participant in the second State Colored Men’s Convention, which met in Nashville in August 1866 and organized daily demonstrations at the Capitol, lobbying legislators to approve their right to vote. It was that dogged pressure, backed by Governor William G. “Parson” Brownlow, who needed the help of black voters in order to win reelection, that convinced the legislature to change the law. Almost overnight African Americans saw a transformation in their civic status. On September 3, 1868, at the beginning of the Circuit Court session, the Nashville Republican Banner published a story titled, “Negro Jurors – A Big Dose of Unadulterated African.” It listed the jurors for the coming term, including Sampson W. Keeble, James C. Napier, and six other African Americans. Keeble’s name also appeared on a list of Grand Jury members in April 1878 and of Federal Court jurors in March and April 1881.

By the time of the 1870 census Sampson Keeble had become the head of a large and complex household. He was the proprietor of the Harding House, a boarding house valued at $4000, a tidy sum for the period. This establishment stood near where the Ryman Auditorium is today. Keeping house was Eliza Keeble, 35, whom we know from their mother’s gravestone to be Sampson’s sister. The individual named Mary, 65, was probably Sampson and Eliza’s mother (usually called Nancy, although her gravestone, as well as this census record, says Mary). She described her occupation as “at home,” and was the only one in the family who unable to read and write. There were two children in the household: Hattie, 8 (ditto marks on the page suggest that her last name was Keeble, but in the 1880 census she was called Hattie Beckwith and identified as a niece), and “Saml” Keeble, Sampson’s son. His age is illegible. It appears to be 4, but is likelier to be 11. Two other women also reside with the family: Kate Beckwith, 22, and Harriet Keeble, 30. Harriet, Sampson’s first wife and the mother of young Samuel, was already an invalid. She died on June 16, 1870, shortly after this census was taken. Her funeral was held at the First Colored Baptist Church on West Martin (Pearl Street) near McLemore Street (10th Ave. N.), with the services conducted by H. S. Bennet and the Reverend Nelson G. Merry, who was the first African American minister ordained in Nashville as well as the founder of the Tennessee Colored Baptist Association. An 1872 Freedman’s Bank record for 13-year-old Thomas Keeble (this was apparently Samuel, since “Sammy” was scratched out and “Thomas” written above it on the form) gave his address as 116 North Cherry Street (today’s 4th Avenue), which was the site of Harding House, and he named as his parents Sampson W. and Harriet Keeble. (See image below.)

Keeble was believed to be among the wealthiest blacks in the city. An 1871 article in the Republican Banner called attention to the fact that a watch stolen from him was evaluated at $100 (the equivalent of as much as $2,000 in 2011). Another article from 1871 suggests that he may have built up his wealth by being sternly frugal. In a squabble with a Market House merchant over the price of a turkey, Sampson Keeble was severely injured when vendor Byron Jackson struck him over the head with a cane. The Nashville Banner reported that Keeble “was taken home mortally wounded,” and that, despite the efforts of physicians who discovered a compound fracture of the skull and “performed the operation of trepanning,” he was not expected to live.

In spite of such grave journalistic predictions, the plucky barber and boarding house proprietor not only survived his injuries but became even more intensely involved in civic affairs during the next two years. In July 1871 Keeble was named a director of the Tennessee Colored Agricultural and Mechanical Association, along with Henry Harding, William Sumner, Elias Polk, Abram Smith, Simeon R. Walker, Nelson Walker, John J. Cary, William Butler, J. W. Lapsley, J. L. Howard, Hiram C. Rhodes, and Oliver Thompson. This association ordered the construction of an amphitheater on the Colored Fairgrounds in preparation for the annual fair, scheduled to open on September 13. In May 1872 the Davidson County Chancery Court issued a decree granting the directors’ petition for incorporation of the association. In June of that year Keeble was re-elected a director as the group planned the next fair, which would open on September 15 and run for six days. Sampson Keeble, now clearly playing a leadership role in the African American community, served as treasurer of the Colored Agricultural and Mechanical Association and as a member of the advisory board of the Nashville Freedman's Savings and Trust Company Bank, one of only a handful of all-black Freedman’s Bank boards in the United States.

A petition was filed in Chancery Court on August 24, 1872, asking that the Freedman’s National Life Insurance Association be incorporated under the following directors: Nelson Walker, John J. Cary, Henry Harding, Abram Smith, Richard Howard, W. C. Napier, Sampson W. Keeble, and William Sumner. “The capital stock of the company is not to be less than $100,000, and may be increased to $250,000, to be divided into shares of $100 each.”

First African American elected to Tennessee General Assembly

Sampson Keeble offered his name as a Republican nominee for a seat in the General Assembly at a Party gathering in July 1869 but lost the nomination to J. H. Sumner, 51-33. He remained active in politics, and his intelligence and good nature won him many friends and supporters. In April 1870 he was on the committee that helped arrange a day of celebration after the adoption of the Fifteenth Amendment. Oddly, Tennessee, which already had a law on its books allowing black male citizens to vote, had voted against the Fifteenth Amendment. [In fact, Tennessee legislators did not ratify that amendment until the 100th General Assembly in 1997!]

The election year of 1872 was a busy time for Keeble. In March he was part of a group of barbers who signed a resolution calling for a state barbers’ convention to get to know one another, to provide for the widows and orphans of deceased members, and “to strive to ameliorate our condition too, and thus contribute our mite to the great work of elevation.” At the convention of the Davidson County Radical Republican Party that endorsed Ulysses S. Grant’s nomination, Sampson Keeble was appointed to the County Executive Committee and was elected as one of the seventeen delegates to the State Convention. In October the members of the Republican County Convention unanimously nominated Keeble, Captain James W. Ready, and Dr. Rudolph Knaffle to be “candidates for the Lower House of the General Assembly of Tennessee,” subject to the approval of the County Republican Executive Committee.

Sampson Keeble’s daughter Jeannette is pictured here with her husband, Benjamin F. Cox, principal of Avery Normal Institute in Charleston, South Carolina, from 1915 to 1936. Jeannette is holding their oldest son, Benjamin, born in 1906. (Photo courtesy of Helen Davis Mills)

A November 2 article in the Nashville Union and American announced, “We have been furnished with one of the genuine Radical tickets for this county — variegated in color and in make-up.” The newspaper urged readers to “vote the straight tickets.”

Thus it was that in November 1872, riding the coattails of a sizeable popular vote for U. S. Grant for President, Sampson W. Keeble was narrowly elected, along with Dr. William P. Jones as Senator, and Philip Lindsley, J. B. Jeup, and James W. Ready as Representatives from Davidson County in the 38th Tennessee General Assembly, which convened on January 6, 1873. Grant was enormously popular among black voters, so Keeble certainly picked up most of those votes, but he must have won a number of white votes as well, from people who found his moderate political stance acceptable. Unlike most other counties that elected black politicians during the next decade or so, Davidson County continued to retain a majority of white voters. Keeble became the first African American to serve as a member of the state legislature (and the last for some time – it would be eight years before another African American member took a seat in the House). The Nashville Union and American reporter who wrote the story on November 7, 1872, was a little careless with his facts and rather ambivalent about Keeble’s victory:

A cynical article from the Clarksville Weekly Chronicle (January 25, 1873) provided some details of the situation Keeble faced in the legislature:

During his term in the legislature, despite such insults by the press and his apparent isolation in the House, Keeble valiantly introduced several bills aimed at bettering the condition of the African American community. One bill was intended to amend Nashville’s charter to allow blacks to operate businesses downtown; a second provided protection for wage earners (several black legislators of the 1880s would later follow his lead and introduce similar bills); and a third appropriated state funds to help support the Tennessee Manual Labor University. However, Keeble was unsuccessful at providing legislation to benefit his black neighbors, for none of his bills received a sufficient number of votes to pass into law. Keeble served only a single two-year term in the General Assembly and lost a later bid for re-election.

When writing about social events that included both black and white guests, several newspapers took note of a Nashville banquet to which Sampson Keeble was invited. According to the Dallas Morning News, “In 1873 Gov. John C. Brown of Tennessee gave a banquet at the Maxwell House in Nashville and one of his guests was Sampson Keeble, a man of very black skin.” The Duluth News-Tribune and the Kansas City Journal said, “In Mr. Cleveland’s first administration the late Frederick Douglass was invited to one of the congressional receptions, together with his Caucasion [sic] wife, then his bride. And John C. Brown, the Democratic governor of Tennessee, as far back as 1873, when he gave a banquet at the Maxwell house, Nashville, had among the invited guests on that occasion the Hon. Sampson Keeble, a black negro representative from Davidshon [sic] county, who not only attended the banquet, but responded to a toast.”

The rise and fall of the Freedman’s Bank

A Freedman’s Bank record for Sampson Keeble’s son Thomas (called “Sam’l” in the 1870 census), a 13-year-old student at Bellview School. Thomas was the son of Sampson and his first wife, Harriet, who died in 1870. No further records of Thomas’s life have come to light. (Heritage Quest Online)

The concept of the Freedman’s Bank was first proposed by abolitionist John W. Alvord at a meeting with business leaders in New York in January 1865. Originally intended as a savings bank for the benefit of African American soldiers, its scope was broadened to include all former slaves and their descendants. Charles Sumner steered the bill quickly through Congress, and it was signed into law by President Lincoln five weeks later, on March 3, 1865. The bank was based in Washington, D.C., but branch offices quickly opened in seventeen states, including Tennessee. Sampson Keeble served from the beginning as a member of the advisory board of the Nashville Freedman's Savings and Trust Company Bank. Advertisements encouraged African American depositors, telling them the bank was chartered by Congress and misleading them into thinking their money was safely under the protection of the federal government. Unfortunately, however, despite the best efforts of Congress and newly appointed bank president Frederick Douglass, the bank had no choice but to close in 1874 because of “overexpansion, mismanagement, abuse, and outright fraud.” (Washington) African American depositors, many of whom had placed their life savings in Freedman’s accounts, were shocked to discover that the federal government did not protect the bank’s assets, and that they had lost everything. Local administrators, powerless to save their banks from the failure of the parent institution in Washington, D.C., petitioned Congress for help.

Sampson Keeble joined the Rev. Nelson Walker, Nashville entrepreneur Henry Harding, and other prominent Nashville citizens in sending a memorial to Congress. In their petition, they attempted to explain the magnitude of the fraud perpetrated on unlettered and trusting depositors by the bank, accusing it of ". . . appealing to a class of people who had been prevented by their previous condition of servitude from accumulating wealth or even a competency; and the principal, and in fact the effective, argument used by the managers and agents of the institution to induce that poor, unlettered, and trusting class to deposit their small earnings—the fruit of their toil—in the institution was, that it was an institution chartered by the Government, with its principal office at the seat of Government, and that its funds, by express direction of Congress, (which the class appealed to believed was a guarantee by Congress,) were to be invested in Government securities. It is easy to see that the colored people, for whose benefit Congress chartered this institution, would readily conclude that the Government was bound or under some pledge which secured their deposits. This may not be the law of the case, but it is certain that such representations were made by the agents of the institution, and that the people who placed their deposits in the bank believed that the Government was bound for the deposits, or at least bound to see that the deposits were securely invested in United States securities, and that this was a contract between the United States and the depositor . . . . There may be no legal obligation resting upon the Government to guarantee [to those left in the unfortunate condition of having every dollar most of them have in the world locked up in the payment of the amounts they have deposited on the faith of their confidence in what they regarded as the solemn pledge of the Government to have the funds of the institution invested in the securities of the Government, but we respectfully urge that there was and is a moral obligation resting on the Government to grant your memorialists, and the other depositors in the institution, speedy relief by assuming and paying the amounts due them; taking the assets of the bank, and holding every other officer or agent of the institution who is liable, civilly or criminally, to a strict responsibility for their acts."

Despite this passionate appeal, joined with similar petitions from other affected states, Congressional response was disappointing. Eventually, about half of the betrayed depositors received a fraction (60% or less) of the value of their accounts, while others lost everything they had saved. A number of depositors continued to petition Congress for years, hoping for reimbursement that never came. In the end, the African American community felt itself betrayed not only by the bank, but also by their government.

Sampson W. Keeble Jr., about 32, with his sister Jeannette Cox's children, Benjamin (4) and Helen (2). The photograph dates from about 1910, shortly before young Keeble moved to Detroit. (Photo courtesy of Helen Davis Mills)

Sampson W. Keeble Jr., about 32, with his sister Jeannette Cox's children, Benjamin (4) and Helen (2). The photograph dates from about 1910, shortly before young Keeble moved to Detroit. (Photo courtesy of Helen Davis Mills)

Civic and political activity

As a result of Keeble’s membership on several boards and his political activism through-out the city, he was well known and admired within the African American community. After his legislative service, he was elected a magistrate in the Davidson County Court, serving from 1877 to 1882. His 1041-1022 victory in 1876 was contested on August 10 by his opponent, James W. Ready, his 1872 Republican running mate, who demanded a recount. After two days of counting Ready’s votes only, election officials announced that his total was 1,060, 19 more than Keeble’s original number. However, as the Daily American pointed out, “Ready should have enjoined the Sheriff from issuing a certificate of election to Keeble, and thus had the matter decided before the returns were made to the authorities at the Capitol. As the Sheriff was not notified of Ready’s intention to contest the election, he gave Keeble a certificate of election, and the returns having been made to the Capitol, Keeble had no trouble obtaining his commission. . . . Ready’s only recourse is now through the courts.” When Ready challenged Keeble’s election in county court August 25, Judge John C. Ferris ruled that the commission could not be set aside once it was granted, and that Keeble should remain in office. Meanwhile, Keeble had asked that his own votes be recounted. This time his total was 1,066 – higher than Ready’s 1,060, after all. On August 22, in the midst of the recount process, Sampson Keeble had again been named a delegate to the State Republican Convention, along with A.V.S. Lindsley, Gen. George Maney, J. C. Napier, and Thomas A. Sykes.

An attack on Keeble’s integrity was reported on November 15, 1878. A story in the Daily American called “Colored Justice under Suspicion” told of the arrest of Keeble and two black police detectives on charges of “extortion and official oppression,” the second such charge against Keeble. It was not unusual for African Americans in positions of authority to be subjected to trumped-up charges by political opponents. It is apparent that these charges were also disproved, for Keeble continued to serve four more years as magistrate without interruption.

His cases were frequently covered by the “Courts” section of local newspapers. One can find articles, for example, recounting that he fined two women for breach of peace in 1877, jailed a man in 1878 for assault and battery, and ordered an inquest in the 1881 death of teenager Granville Bosley, who had been struck by lightning. In 1877 Keeble’s office was the site of a protest meeting of journeymen barbers, who initiated a strike for higher wages and more equitable working conditions.

Sampson Keeble ran again for the General Assembly in 1878 but was defeated by a Greenback party candidate, perhaps partly because the Democrats were beginning to regain their political supremacy in Davidson County by that time, and partly because racial violence and poll taxes were producing their intended effect of intimidating black voters, who failed to turn out at the polls in their usual numbers. Keeble remained active in city government, however, serving on a federal grand jury in 1881 and eventually being elected as a magistrate.

Marriage to Rebecca Cantrell Gordon

(Photo courtesy of Helen Davis Mills)

By the time of the 1880 census, Sampson, now in his late 40s, was married to Rebecca Cantrell Gordon, a 29-year-old teacher (born August 24, 1849), who had been educated in New York; they were the parents of three-year-old “Jennie” (Jeannette) and one-year-old “S.W.” (Sampson W. Jr.). These were the only Keeble children who survived to adulthood. Several others, including a set of twins, died in infancy. (Five-month-old Charles Marshall Keeble died in November 1881; another son, born during the election year of 1884, was given the name James G. Blaine Keeble, but this child soon died as well.) In the 1910 census, Rebecca would report that only two of the six children to whom she had given birth were still living. Also residing in the Keeble household in 1880 were Sampson’s widowed mother, Nancy Keeble (78), and two young relatives, Hattie M. Beckwith (18, doubtless the 8-year-old Hattie “Keeble” of the previous census) and Maggie K. Smith (17), both of whom were attending school in Nashville. Everyone in the household except for Sampson was identified as “mulatto.”

Keeble’s wife Rebecca was the natural daughter of her mother Harriott’s slave-owner, Carroll McGuire [named on her death certificate], and was raised in her father’s home, with light duties as a household servant – a “foot slave.” It is quite possible that she was educated along with the other children of the household. Delighted by this clever little girl, her father sent her to live with relatives in Staten Island, New York, and she received an education there that included lessons in music and Latin. She eventually returned to Nashville (after a failed romance, according to family lore) where she began to teach other African Americans, both children and adults, to read and write. Even after the Civil War, a considerable number of people opposed education for blacks, and some extremists attempted to find and close black schools, which were often makeshift workshops held in churches and private residences. Rebecca continued to teach, in spite of threats to her safety, moving from place to place to meet with her students. Sampson Keeble fell in love with this beautiful and spirited young woman, more than 15 years his junior, and they were married about 1875. Family members say that both Sampson and Rebecca were avid readers who particularly loved reading the Bible.

Family life and children’s accomplishments

At some point, daughter Jeannette remembered, the family left Nashville for Marshall, Texas. However, they returned to Nashville a short time later when, as descendants tell the story, the passionately Republican Keeble “was run out of there for being a rabble-rouser.” Jeannette may have been remembering her father’s final years – he died in Fort Bend County, Texas, in 1887, when his children were still quite young. Rebecca returned to Nashville and continued to work after becoming widowed. She was a remarkable seamstress, and could knit, crochet, tat (make lace), and embroider expertly. Her name appeared in city directories from 1891 through 1918 in much the same form: “Keeble, Rebecca G (c), widow Samson W, seamstress,” and her address for much of that period was a boarding house at 1605 Jefferson Street. Her son Sampson W. Jr. lived with her until 1910 or 1911. Keeble descendants remember that he owned a high-wheeler (penny-farthing) bicycle as a young man. There were a number of these bicycles around Nashville during the 1880s, as well as clubs that encouraged their use.

Benjamin and Jeannette Keeble Cox, both graduates of Fisk University, were lifelong educators, spending many years at the helm of the Avery Institute in Charleston, South Carolina. Sampson Jr. appeared from time to time in Nashville city directories, working as a porter, a clerk, or a messenger (for the Duncan Hotel); his last Nashville census entry was recorded in June 1910, showing him to be single and living in Rebecca’s household. In August 1912 he took out a license in Detroit, Michigan, to marry Alice Criss, a woman who had been married once before. Keeble gave his age as 34, listed his occupation as janitor, named Sampson and Rebecca as his parents, and stated he had no previous marriages. C. Emery Allen, clergyman, officiated at the ceremony, held August 18, 1912. Unfortunately, when Sampson filled out his Draft Registration card in 1918 (medium height, medium build, brown eyes, black hair), his marriage seems to have ended. He listed Rebecca Keeble as his nearest relative, and his occupation as porter in the Hoffman Hotel in Detroit. Alice’s name appeared on another marriage license in July 1920; 40 years old by then, and marrying a 33-year-old laborer named Ralph Dixon, she said (for the second time!) that she had had only one previous marriage.

Final years

Gravestone of Benjamin Cox illustrating his marital relation to Jeannette Keeble Cox; daughter of Sampson W. Keeble.

Gravestone of Benjamin Cox illustrating his marital relation to Jeannette Keeble Cox; daughter of Sampson W. Keeble.

After her son moved north, Rebecca continued to work as a dressmaker. When her eyes failed, Jeannette and Benjamin Cox took her into their home in Charleston, where she could be near her beloved grandchildren. She died there tragically, early in 1923, when a gas stove in her room set her clothes on fire. Although family members rushed to her aid, they were too late to save her.

The last year the name of Sampson Keeble Sr. appeared in the Nashville City Directory was 1886, when he was listed as a teacher. A brief obituary in the Nashville Daily American on July 3, 1887, said, “The many friends of Sampson W. Keeble (formerly of Nashville) will regret to learn of his sudden death, which occurred in Richmond, Tex., June 19, caused by a congestive chill [probably a form of malaria]. He was born in Rutherford County May 18, 1833. He was 54 years old.”

It is not clear whether Sampson W. Keeble was buried in Texas or Tennessee. He is listed with his daughter and son-in-law, Jeannette Keeble and Benjamin F. Cox, on a grave-stone in Greenwood Cemetery on Elm Hill Pike in Nashville. The grave is on a piece of land that runs parallel to Spence Lane, directly across from the final resting places of R. H. Boyd, a Nashville publishing giant, and James C. Napier, the city’s first African American councilman and Register of the U.S. Treasury under President Taft. There is no grave for Rebecca, although her death certificate says that her body was returned to Nashville for burial on January 10, 1923, so it is probable that Sampson was already buried in that city. Sampson’s mother lies in the old Mt. Ararat Cemetery in Nashville, under a broken gravestone with this nearly illegible inscription:

|

KEEBLE Born: 1805 Died: 1883 SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF MA??M THE MO????OF S. W./ ELIZA A. CEORCEL KITTY ????Y KEEBLE BORN IN CUMBERLAND CO. VA. AUG. 20, 1805 DIED IN NASHVILLE JAN. 16, 1883 LORD ? CHRIST <><><><><> |

State Honors Sampson Keeble in 2010

On Monday, March 29, 2010, a bust of Sampson W. Keeble, commissioned by the Tennessee Black Caucus of State Legislators, was unveiled outside the House Chamber in the State Capitol. Created by internationally recognized sculptor Roy W. Butler, the bust stands on a base of Tennessee pink marble engraved with the names of all fourteen African American legislators elected to the Tennessee General Assembly during the 19th century. The day-long ceremony, which was attended by eight direct descendants of Sampson Keeble, included addresses by three historians, a slide show by Mr. Butler illustrating various stages in the production of the bust, a luncheon for family members and legislators at the historic Hermitage Hotel, and the unveiling of the statue, followed by a public reception and the reading of a proclamation in the House of Representatives honoring Keeble and the other 19th century black legislators.

Many thanks to Sampson Keeble family members Helen Davis Mills, Dr. Leonard Davis, and Dr. Wendell Cox Jr., who provided invaluable information for this biography. We are so very grateful for your continuing support.

Much gratitude also to Walter Keeble descendant Virginia G. Watson for sharing her research on the Keeble family.

Sources:

“All about a Turkey,” Nashville Republican Banner, February 7, 1871.

“All Sorts of Items,” San Francisco Bulletin, March 6, 1874.

“Barbers’ Convention,” Nashville Union and American, March 27, 1872.

Burkholder, Mary Ann. The “Stony Lonesome” Letters, 1987. Typescript in the collection of the Tennessee State Library and Archives.

“The Can Can: The Stokes Pow-Wow at the Courthouse Yesterday,” Nashville Republican Banner, July 11, 1869.

Cartwright, Joseph H. The Triumph of Jim Crow: Tennessee Race Relations in the 1880s. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1976.

“The Colored Fair,” Nashville Republican Banner, July 16, 1871.

“The Colored Farmers,” Nashville Republican Banner, June 6, 1872.

“Colored Justice under Suspicion,” Nashville Daily American, November 15, 1878.

“The Colored Member of the Legislature,” Clarksville Weekly Chronicle, January 25, 1873 (Correspondence of the Courier-Journal, Nashville, January 14, 1873).

“The Contested Magisterial Race,” Nashville Daily American, August 15, 1876.

“The Courts,” Nashville Daily American, April 17, 1878.

“The Courts,” Nashville Republican Banner, May 15, 1872.

Dallas Morning News, October 25, 1901.

“Death of Sampson W. Keeble,” Nashville Daily American, July 3, 1887.

“Democratic Precedents,” Duluth News-Tribune, October 27, 1901.

“Died,” Nashville Republican Banner, June 17, 1870.

“Died.” Nashville Daily American, November 11, 1881.

Fayetteville Observer, November 21, 1872.

“The Federal Court Grand Jury,” Nashville Daily American, April 28, 1881.

“Federal Court Jurors,” Nashville Daily American, March 16, 1881.

“The Fifteenth Amendment: Programme of our Colored Citizens for Celebrating its Adoption,” Nashville Republican Banner, April 27, 1870.

Freedman’s Bank records, Ancestry.com.

“Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company,” Report No. 58, U.S. House of Representatives, 43rd Congress, 2nd Session, December 7, 1874-March 4, 1875.

“The Freedmen’s National Life Insurance Company,” Nashville Republican Banner, August 25, 1872.

“Grant Indorsed: Proceedings of the Radical County Convention,” Nashville Republican Banner, May 12, 1872.

“History of a Stolen Watch,” Nashville Republican Banner, October 18, 1871.

“In Chancery at Nashville,” Nashville Republican Banner, September 3, 1872.

“Instantly Killed: Granville Bosley, colored, Laid Low by an Electric Stroke,” Nashville Daily American, August 14, 1881.

“Keeble Still Ahead,” Nashville Daily American, September 2, 1876.

Lovett, Bobby L. The African-American History of Nashville, Tennessee, 1780-1930: Elites and Dilemmas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

McBride, Robert M., and Dan M. Robinson. Biographical Directory, Tennessee General Assembly, Volume II (1861-1901). Nashville: Tennessee State Library and Archives, and Tennessee Historical Commission, 1979.

Nashville Banner, April 23, 1886.

Nashville Daily American, October 21, 1876; March 30, 1877; August 30, 1878; November 3, 1878; November 6-7, 1878; November 4, 1880.

Nashville Republican Banner, June 17, 1872; September 10, 1872; November 6, 1872.

Nashville Union and American, November 10, 1870; September 6, 1872; September 29, 1872; November 7, 1872; June 7, 1873; October 11, 1873; February 14, 1875.

“Negro Jurors,” Nashville Republican Banner, September 3, 1868.

“The Probable Result,” Nashville Republican Banner, November 8, 1872.

Rabinowitz, Howard N. Race Relations in the Urban South, 1865-1890, 2nd ed. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1978, 1996.

“The Radical Ticket,” Nashville Union and American, November 2, 1872.

“Ready vs. Keeble,” Nashville Daily American, August 12, 1876.

“Representative Keeble,” Nashville Union and American, December 6, 1872.

“Representative Keeble,” Pulaski Citizen, December 18, 1872.

“Republican Nominations for the Legislature,” Nashville Union and American, October 24, 1872.

“Repudiating the Ring,” Nashville Republican Banner, September 4, 1868.

Scott, Mingo Jr. The Negro in Tennessee Politics and Governmental Affairs, 1865-1965: "The Hundred Years Story.” Nashville: Rich Printing Co., 1964.

“South Criticises,” The Daily Review (Decatur IL), October 18, 1901.

“Stony Lonesome, the Keeble Family Home,” Middle Tennessee Journal of Genealogy & History, Vol. XXII, No. 1, 2008.

Taylor, Alrutheus Ambush. The Negro in Tennessee, 1865-1880. Washington, D.C.: The Associated Publishers, 1941.

Tennessee General Assembly. Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Tennessee. Nashville: Tavel and Howell, 1881, 1883.

“That Insurrection,” Nashville Republican Banner, October 17, 1866.

“To the Barbers of the State of Tennessee,” Nashville Union and American, March 6 and 19, 1872.

“Visitors to Grant,” Cincinnati Daily Gazette, March 4, 1869.

Washington, Reginald. “The Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company and African American Genealogical Research,” Prologue Magazine, Special

Issue on Federal Records and African American History, Summer 1997, Vol. 29, No 2.

Watson, Virginia Gooch. The Keeble Family Genealogy, 1986. Typescript in the collection of the Tennessee State Library and Archives.

Weekly Louisianian, November 30, 1872.

Work, Monroe N. “Some Negro Members of the Tennessee Legislature During Reconstruction Period and After.” Journal of Negro History, Vol. V, January 1920, 114-115.