Birth into slavery

Birth into slavery

William A. Feilds, born in West Tennessee in 1852, was elected to represent Shelby County in the 44th Tennessee General Assembly, 1885-1886. Although many records spell his surname as “Field” or “Fields,” William himself seems generally to have used the “e-i” combination, also generally adding a final “s,” as can be seen in surviving legislative records. In view of the fact that William Feilds’s parents were born in Virginia (1880 census), it is probable that he was descended from the same group of slaves as former Tipton County Representative John Boyd (42nd Tennessee General Assembly, 1881-1882). Boyd’s mother, Sophia Fields* Boyd, was the slave of Jean Field Sanford, who was a young child in 1836 when her father, Charles Grandison Feild, moved his household from Mecklenburg County, Virginia, to Haywood County, Tennessee. Several of Charles G. Feild’s family members, including his nephew Roscoe Feild, lived in the same part of Shelby County as William and his family.

Marriage and family

On December 29, 1874, 22-year-old William A. Feilds married Elizabeth (Lizzie) Fields, age 20 [Shelby County Marriage Book F, p. 504]. Elizabeth’s brother, Bland Fields, signed their marriage bond. Lizzie and Bland’s father was born in Virginia, as were most of the older Feild slaves (giving further credence to the theory that they had been brought to Tennessee by Charles G. Feild). It is noteworthy that William and Bland (both born about 1852) were able to sign their names to the marriage certificate, since many former slaves had still not learned to read or write by that time. The minister who conducted William and Elizabeth’s marriage ceremony was the Reverend Page Tyler, perhaps the inspiration for the name of Tyler’s Chapel Cemetery where, forty years later, Elizabeth’s children would bury her.

Elizabeth’s death certificate named her father as “John,” and said her mother was “Unknown.” Her parents may, in fact, have been the John (40) and Judy (35) Feilds who appeared in the 1870 census, living in District 6, Shelby County. Elizabeth would be the “Bettie” (17) of that census; four other children were listed: Richard (21), John (14), Alice (12), and Ida (10). Elizabeth’s brother Bland (18) showed up that year in the household of William and Julia Smith, District 15, Shelby County. William Smith, who was white, was a 40-year-old lawyer with five children, ages 6 to 16. The family employed six servants, ages 16 to 43, all of whom were identified as either black or mulatto.

By the time of the 1880 census, William and Elizabeth “Field” were living in the 6th Civil District of Shelby County. Three children had joined the family by this point: Mary L. (4), Cyrus William (2) and infant Stella A.V. Also living in the household were Elizabeth’s brother Bland and ten-year-old Julia Field, identified as a cousin. (Julia was said to be working as a nurse, so an error must have occurred in the transcription of her age information.) William listed his profession as school teacher, and Bland was working as a farmer.

In 1882 Sholes’ Memphis City Directory listed Feilds as a “teacher 5th District school, r county.” According to the 1883 (Sholes) and 1884 (Weatherbe) city directories, William A. “Fields” was employed as the principal of Shelby County’s 5th District school, which was sited during those years on Waldran Avenue (now Waldran Boulevard) just beyond the Memphis city limits (probably not far from where Memphis Central High School stands today).

Election to Tennessee General Assembly

William A. Feilds was 32 years old in 1884 when he was elected to a single term in the Tennessee General Assembly. A flattering news article appeared in the Cleveland Gazette: “The legislature of Tennessee has among its members three colored members, Mr. McElwee, Mr. Fields, and Mr. Green E. Evans. These three gentlemen are all school teachers, and give evidence of aspirations to become lawmakers. They are young, ambitious and full of zeal, and if an opportunity is given may prove themselves equals and superiors of many Tennessean Senators before the adjournment of the present session.” The Memphis Daily Appeal was not so kind: “W. A. Fields is of a bright copper color, and besides the business of accumulating a considerable family has been a professional school teacher and an active participant in county Republican conventions. He lives near the National Cemetery, and has no wealth to speak of beyond a fair supply of words and a tolerable knowledge of English grammar.

Feilds was appointed to three legislative committees: Federal Relations, Internal Improvement, and Public Roads. He followed the lead of his cousin John Boyd in attempting to amend some of the Tennessee labor laws that effectively maintained many blacks in bondage to their white landlords. One of his bills proposed to limit the amount of lien a landlord could impose on tenants’ crops – existing laws allowed land owners to bankrupt tenant farmers by requiring excessively large debt payments. He also introduced a bill to enforce greater integrity in the hiring process. Former slaves, unaccustomed to working for pay, were frequently exploited by employers who advertised high wages for a job and then paid laborers much lower amounts once they were hired. A third bill attempted to ensure fair elections by requiring voting sites to be overseen by judges from different political parties. As many African American candidates and voters would soon learn to their dismay, election fraud was commonplace, particularly among white Democrats who were steadily gaining control of the polls in West Tennessee counties with large black (hence Republican) populations.

Of particular interest to teacher-principal Feilds were legislative efforts to educate black children successfully and to give African Americans greater control over the schools in their communities. He urged passage of his bill, HB 119, which would require parents and guardians to enroll children aged 7-16 in school for 120 days per year. Other legislators also sponsored education bills during that term. For example, Representative Greene Evans promoted a bill, written at the request of Governor Bate, to create the position of Assistant Superintendent of Public Instruction to oversee the black schools across the state. Although Evans introduced the bill in both the regular and extraordinary sessions of the 44th General Assembly, and the governor urged its passage in his State of the State address that opened the session, it was never voted into law. In fact, it was rare for a black legislator’s bill to be enacted, particularly if it broadened the rights or protections of black citizens. Of the few bills that were successful, some were eventually amended so drastically that even the sponsors voted against them! William A. Feilds’s bills were no exception to this rule: three of them failed or were tabled in committee; the fourth was rejected on its third reading before the House.

Feilds also supported the efforts of his colleagues, Representatives Evans and Hodge, to repeal Chapter 130 of the 1875 Acts of Tennessee, which permitted segregation in public facilities and transportation. At least one bill aimed at overturning Chapter 130, Tennessee’s first “Jim Crow” law, was introduced in every session to which black legislators were elected, but none ever received sufficient votes to pass.

Feilds’s name was read into the record on Tennessee Day at the 1885 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition, but it is not clear whether he was in attendance there.

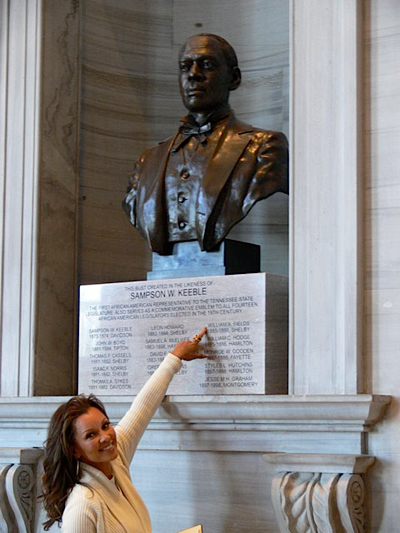

(Photo courtesy of Vanessa Williams)

Later years

To the eternal dismay of researchers, the 1890 census, which would surely have provided valuable information about the Feilds family, was destroyed in a fire in 1921. Complicating matters even further is the presence in census records of another Memphis couple named William and Elizabeth Feild. This William, a laborer who lived at 982 Delaware Avenue, died in 1909 of pneumonia.

By the time of the 1900 census, Elizabeth (Lizzie) Feilds had become a widow. She and six of her children – Mary (24), Silas W. (22), Estell (the “Stella A.V.” of the 1880 census, now 20), Luther (18), Ida (16), and Bland (12) – were living with her brother Bland and his family at that time. Bland (48) and his young wife, Jennie V. (25) had an infant son by now – John B., three months old.

William and Elizabeth’s oldest son Cyrus enlisted that same year (1900) in the U.S. Army. He was stationed at Fort Reno, Oklahoma, as one of the famed “Buffalo Soldiers” of the 25th Infantry, an African American unit in what was still a segregated Army. As a member of that regiment, although he entered too late to participate in the Cuba campaign of the Spanish American War (which included the unit’s action at the famous Battle of San Juan Hill), he might have taken part in quelling the Creek Rebellion and capturing Creek leader Chitto Harjo (“Crazy Snake,” 1846-1911) and others. Cyrus Feild was probably also sent to the Philippines to participate in operations against nationalist leader Emilio Aguinaldo. Notes from the U.S. Army Register of Enlistments document his promotion to sergeant, his honorable discharge in 1903, and his service rating of “Excellent.” Cyrus (32) later appeared in the 1910 census with his wife (Sadie, 30) and three young children: Mary E. (4), William (2), and Cyrus Jr. (1), and was listed as the “informant” on his mother’s death certificate (she died of lobar pneumonia) in March 1914. Cyrus Feild himself died at the age of 77 and was buried in the Memphis National Cemetery in January 1956.

William A. Feilds had a much briefer life than his son. There were no city directory entries for the senior Feilds from 1885 to 1891, when he appeared in the Polk Directory as a Justice of the Peace. In 1894 (Polk) he was also listed as a Notary Public, and in 1898 as Justice of the Peace (Polk), as well as a County Magistrate (Degaris), with his office on Charleston Avenue and his home on the Old Raleigh Road, east of the city. A magistrate in a rural county during those years was the equivalent of what we now think of as a “county commissioner.” He could issue warrants and hear minor criminal cases, perform marriages, and appoint guardians and administrators to help to settle estates. Magistrates were also part of the local legislative body that approved all county expenses and passed county laws and ordinances. In the 19th and early 20th centuries they were thought of as a “court” because of their judicial duties; in recent years, as county governments have assumed a more complex role, the magistrates/commissioners tend to be considered more of a legislative body.

Shelby County Court Resolution

The 1899 Polk City Directory published William Feilds’s death date as September 10, 1898, although a County Court resolution (below) said it was a day earlier, September 9. Feilds was only 46 years old. After his death a committee representing the Shelby County Court published a resolution honoring his many years of service. Addressed “To the Worshipful County Court, Quarter Session, Oct. Term 1898,” the document, which contains several inaccuracies, reads as follows:

William A. Fields [sic] was born near Fisherville in Shelby Co. about fifty two [46]

years ago. At the close of the War he came to the 6th Dist. to live with a relative,

John Fields, where by unremitting labor and close application to study, he quali-

fied himself to teach in the public schools. In 1878 [1884] he was elected a

member of the Legislature from Shelby County and served in that body during

the memorable Session of 1879. [1885] In 1888 he was elected a member of

this Court from the 6th Civil District, re-elected in 94 and continued as an active

member until Sept. 9, 1898, when a Summons from the highest of all tribunals

called him from the mystery of life to the deeper mysteries of death. In addition

to the other responsible positions which he so worthily filled was that of Census

taker in 1890 for the Sixth district. His wife was a sister of Bland Fields, who

with six children survive him.

Unpretentious and modest as he was, he was scarcely appreciated, except by those

who knew him intimately. In all the relations of life he was faithful and true, discharging with fidelity every trust confided to his keeping. A loyal, humble and

consistent communicant of the Episcopal Church, his daily walk and conversation

was a living illustration of its teachings and his peaceful death gave consoling

assurances that after life’s fitful dream he sleeps well and that his immortal Spirit

has entered upon that record of well done good and faithful Servant. While he has

not left large earthly riches to his afflicted family, he has bequeathed them a legacy

more precious than gold, more imperishable than monumental brass, a spotless name.

Wherefore, be it resolved that with the death of W. A. Fields, this Court has lost

a useful and respected member, the county a valuable and honored citizen and his

family a devoted husband and father.

Resolved that the foregoing report be spread upon the Minutes of this Court and

the Clerk thereof be instructed to certify a copy of same to the widow of deceased.

Tom Holeman

A. R. Pope

N. F. Ford, J.P.

*Note: many of the Feild slaves changed the spelling of their surnames to “Field” or “Fields” after the Civil War. We are not certain whether they made the change in order to use a more standard form or to distance themselves from their slave identities. One of William Feilds’s descendants is actress/singer Vanessa Williams, whose story was featured on the NBC genealogy series Who Do You Think You Are? in February 2011.

Derived from the research of John W. Marshall, Memphis, TN, author of The Early History of Mason (1985) and Mason: A Glimpse into the Past (1991). KBL 11/06/2012

Sources:

Cartwright, Joseph H. The Triumph of Jim Crow: Tennessee Race Relations in the 1880s. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1976.

Cleveland Gazette, January 24, 1885.

McBride, Robert M., and Dan M. Robinson. Biographical Directory, Tennessee General Assembly, Volume II (1861-1901). Nashville:

Tennessee State Library and Archives, and Tennessee Historical Commission, 1979.

Memphis City Directories.

Tennessee General Assembly. Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Tennessee. Nashville: Tavel and Howell, 1881, 1883.

“Who They Are—Sketches of the Recently Elected Senators and Representatives from This County and District,” Memphis Daily Appeal,

November 13, 1884.

“World’s Exposition,” Times-Picayune, March 14, 1885.